– Transparent Territory

– Vehicle

– Calligraphy and Cartography

– Nearfar Object

– Ecstatic Cartography

– Feral Map

– Vertical Aerial

– Agglomorate

– Depths in Feet

– Garden Carpet / Prayer Carpet

– Sculpture

– Vehicle

– Calligraphy and Cartography

– Nearfar Object

– Ecstatic Cartography

– Feral Map

– Vertical Aerial

– Agglomorate

– Depths in Feet

– Garden Carpet / Prayer Carpet

– Sculpture

LESSONS IN LOOKING DOWN

Text by Mark Gevisser

“Look down!” shouts Jules Verne’s Professor Lidenbrock to his nephew Axel in Chapter V of Journey to the Centre of the Earth. “Look down well! You must take a lesson in abysses.”

Liddenbock and his nephew, Axel, are in Copenhagen to train for their expedition by spending five days climbing the city’s Church of Our Saviour, to conquer their vertigo: “I opened my eyes,” reports Axel of his first ascent. “I saw houses squashed flat as if they had all fallen down from the skies; a smoke fog seemed to drown them. Over my head ragged clouds were drifting past, and by an optical inversion they seemed stationary, while the steeple, the ball and I were all spinning along with fantastic speed….. All this immensity of space whirled and wavered, fluctuating beneath my eyes.”

Gerhard Marx’s exhibition Lessons in Looking Down, which draws its title from the chapter above, is a lesson in vertigo. Marx isworking with maps and satellite photographs, aerial views of Johannesburg. But he is an artist, not a cartographer, he reminds me: “I like to take images from the represented world, images like maps and botanical drawings, and return them to a subjective, emotional, human space.”In other words: to use maps counter-intuitively, to provoke a sense of dislocation, of the vertigo that comes from looking down at a great height, of the terror of losing one’s bearings but also the thrill of losing one’s way. His intention is not to help us find our way, but to get us lost in his dense web of lines.

Liddenbock and his nephew, Axel, are in Copenhagen to train for their expedition by spending five days climbing the city’s Church of Our Saviour, to conquer their vertigo: “I opened my eyes,” reports Axel of his first ascent. “I saw houses squashed flat as if they had all fallen down from the skies; a smoke fog seemed to drown them. Over my head ragged clouds were drifting past, and by an optical inversion they seemed stationary, while the steeple, the ball and I were all spinning along with fantastic speed….. All this immensity of space whirled and wavered, fluctuating beneath my eyes.”

Gerhard Marx’s exhibition Lessons in Looking Down, which draws its title from the chapter above, is a lesson in vertigo. Marx isworking with maps and satellite photographs, aerial views of Johannesburg. But he is an artist, not a cartographer, he reminds me: “I like to take images from the represented world, images like maps and botanical drawings, and return them to a subjective, emotional, human space.”In other words: to use maps counter-intuitively, to provoke a sense of dislocation, of the vertigo that comes from looking down at a great height, of the terror of losing one’s bearings but also the thrill of losing one’s way. His intention is not to help us find our way, but to get us lost in his dense web of lines.

Not unsurprisingly, Marx is deeply interested in the tradition of flânerie, of wilfully losing one’s way in a city. One of his favourite quotes is Walter Benjamin’s famous observation that while not finding one’s way around a city is something that anyone can do, to actually “lose one’s way in a city, as one loses one’s way in a forest, requires some schooling.” The suggestion of the flâneur’s deliberation and practice and patience, rather than his vague and impetuous wandering, is particularly helpful in understanding Marx’s work, given its intense and obsessive ordering of materials.

Perhaps Marx got his idea for his “Garden Carpet” series from Benjamin, for the above quote continues: “Street names must speak to the urban wanderer like the snapping of dry twigs, and little streets in the heart of the city must reflect the times of day, for him, as clearly as a mountain valley. This art [the art of getting lost] I acquired rather late in life; it fulfilled a dream, of which the first traces were labyrinths on the blotting papers in my school notebooks.”

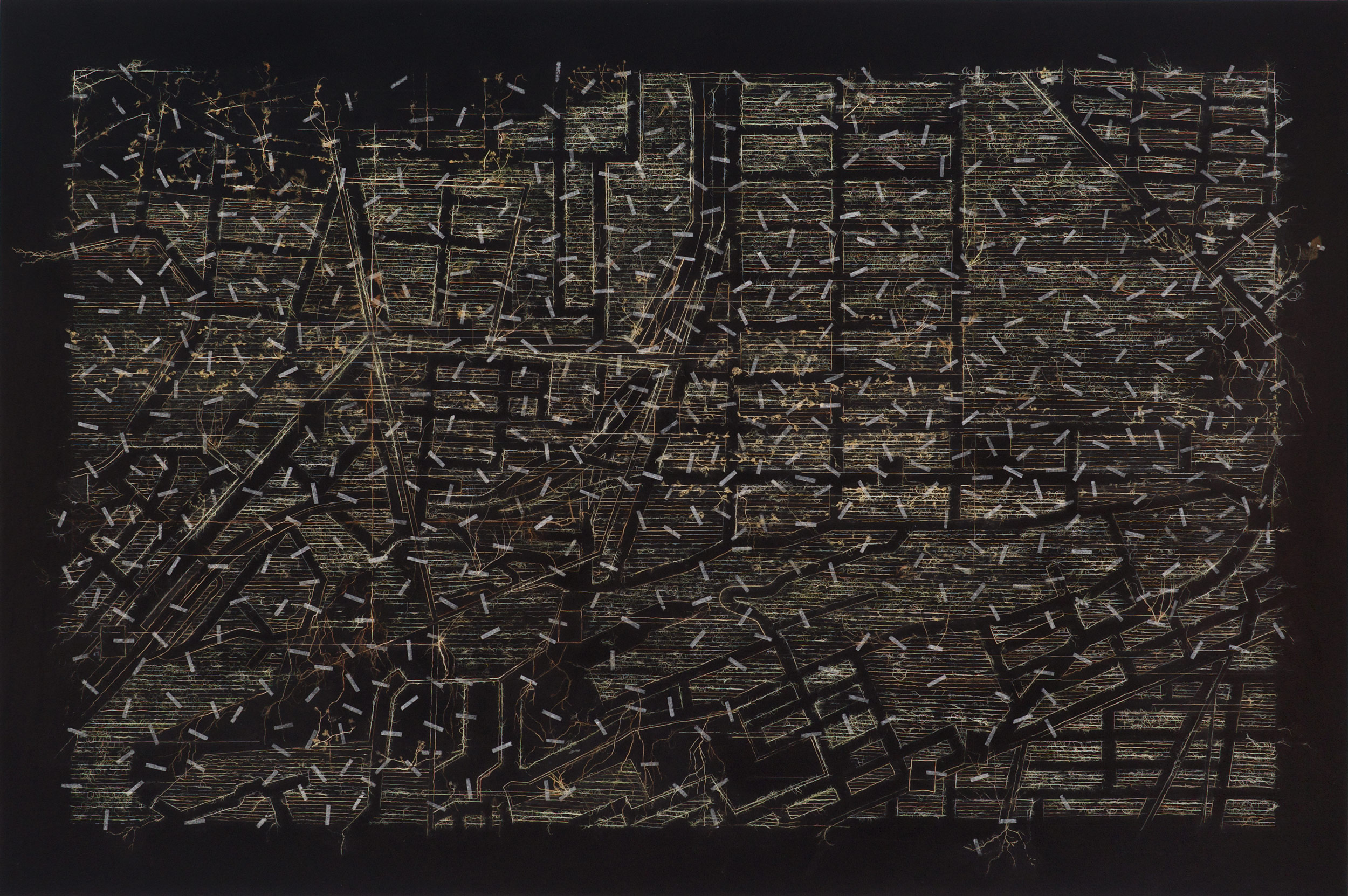

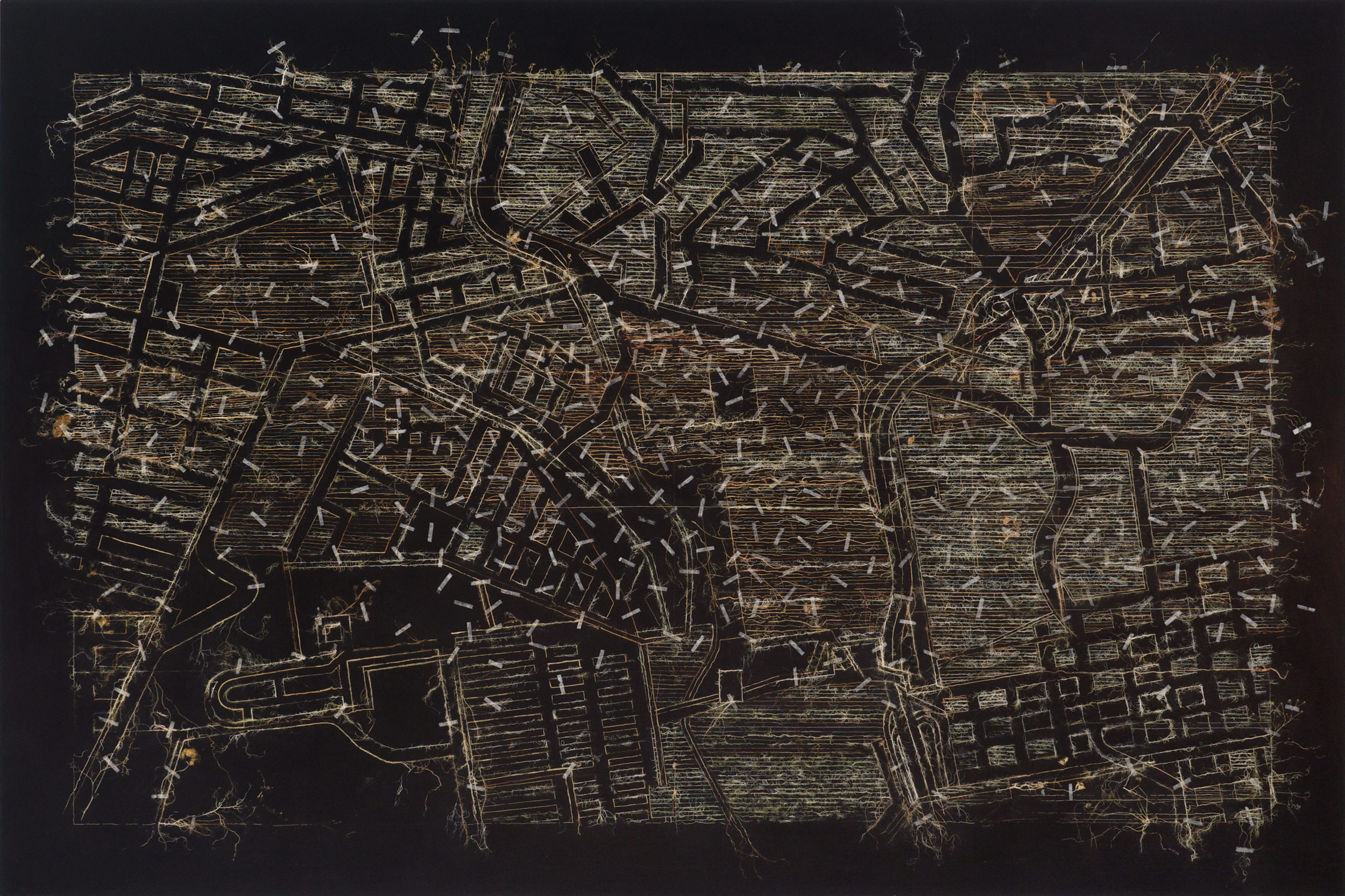

As always in Marx’s work, the artist’s choice of materials is not merely a formal consideration. In “Garden Carpet” he draws the street-plan of the city with plant material that he foraged off sidewalks and building lots or harvested off the mountain side in Cape Town, where he currently lives. He pulls these organic materials into lines, which he embeds into a base of paint and glue like luminous fossils, like x-rayed synapses in the darkness of a brain, like the jewels of a city viewed from an aeroplane at night.

Perhaps Marx got his idea for his “Garden Carpet” series from Benjamin, for the above quote continues: “Street names must speak to the urban wanderer like the snapping of dry twigs, and little streets in the heart of the city must reflect the times of day, for him, as clearly as a mountain valley. This art [the art of getting lost] I acquired rather late in life; it fulfilled a dream, of which the first traces were labyrinths on the blotting papers in my school notebooks.”

As always in Marx’s work, the artist’s choice of materials is not merely a formal consideration. In “Garden Carpet” he draws the street-plan of the city with plant material that he foraged off sidewalks and building lots or harvested off the mountain side in Cape Town, where he currently lives. He pulls these organic materials into lines, which he embeds into a base of paint and glue like luminous fossils, like x-rayed synapses in the darkness of a brain, like the jewels of a city viewed from an aeroplane at night.

1

2

These cityscapes are depopulated, as maps are, and yet they oscillate with life. Up close, the lines reveal themselves to be woven of several strands, and they shimmer as if they were a photograph of moving lights along night-time streets, or the pulse of electricity pumped along a grid. From a distance, the paper tabs that seem to be pinning down the

map seem to be a swarm of ants.

The tabs are used to evoke the way scientists in herbariums hold down plants after they have pressed them flat. They give the impression that the map might fly off the page at any moment if not held down; that humanity’s endeavours, in making maps or making cities or ordering nature, are just a wind’s breath away from chaos and disorder – or, more accurately, from returning to the order of the natural world, where there is no grid.

Marx calls his works “Garden Carpet”in an allusion to the carpets woven in silkand wool, from ancient Persia, that nomadic travellers would carry with them to remind them of the utopian perfection of the urban gardens left behind as they wandered into thewilderness. In a way, his “garden carpets” are the inverse, for they are cityscapes woven with roots and shoots. Cities are made, usually, as people clear paths through the brush, just aside as are made as we clear neural pathways through the bushveld of our brains. In Marx’s work it is the other way round: the contours of his cities are drawn with brush. Similarly, the emotion we feel as we lose ourselves in these landscapes sparks synapses in the way thelogical reading of a map never could.

The tabs are used to evoke the way scientists in herbariums hold down plants after they have pressed them flat. They give the impression that the map might fly off the page at any moment if not held down; that humanity’s endeavours, in making maps or making cities or ordering nature, are just a wind’s breath away from chaos and disorder – or, more accurately, from returning to the order of the natural world, where there is no grid.

Marx calls his works “Garden Carpet”in an allusion to the carpets woven in silkand wool, from ancient Persia, that nomadic travellers would carry with them to remind them of the utopian perfection of the urban gardens left behind as they wandered into thewilderness. In a way, his “garden carpets” are the inverse, for they are cityscapes woven with roots and shoots. Cities are made, usually, as people clear paths through the brush, just aside as are made as we clear neural pathways through the bushveld of our brains. In Marx’s work it is the other way round: the contours of his cities are drawn with brush. Similarly, the emotion we feel as we lose ourselves in these landscapes sparks synapses in the way thelogical reading of a map never could.

With these inversions, Marx is drawing us into the dialectic between wilderness and order; a dialectic usually resolved by a garden, resolved by a map, but in this case utterly upended by his “Garden Carpet”. The exhilirating poetry of this works happens in corners where weeds seem to fly off the two-dimensional grid and climb towards heaven, or where roots plumb down into the earth; in the way that line, woven rather than drawn, is perpetually breaking its bounds. The earth itself, beneath the map, seems to be on fire, illuminating the surface scratchings from within.

Marx refers frequently to an observation by Walter Benjamin: looking down is an analytical experience, while looking ahead is an emotional one. This is why we unfold maps on a table, while we hang landscapes on a wall. With “Garden Carpet” and with “Vertical Aerial”, Marx confounds the two; this is why he has tilted his maps into the vertical plane, so that we can engage with them more emotionally. He hangs his “Garden Carpet” on the wall, and he folds his “Vertical Aerial” along a crease so that can stand up, off the floor.

In “Vertical Aerial” Marx plots the city, off an aerial photograph, with tesserae of stone and tile. What is a city, after all, if not an agglomeration of shards and fragments blown in from other places and reconstituted to form a new whole, a new pattern? Marx practises a form of cartographic pointillism with his mosaic: the city is sharply in focus when viewed at distance, but pixilates into blur –as the city itself does – the closer we get to it.

Marx refers frequently to an observation by Walter Benjamin: looking down is an analytical experience, while looking ahead is an emotional one. This is why we unfold maps on a table, while we hang landscapes on a wall. With “Garden Carpet” and with “Vertical Aerial”, Marx confounds the two; this is why he has tilted his maps into the vertical plane, so that we can engage with them more emotionally. He hangs his “Garden Carpet” on the wall, and he folds his “Vertical Aerial” along a crease so that can stand up, off the floor.

In “Vertical Aerial” Marx plots the city, off an aerial photograph, with tesserae of stone and tile. What is a city, after all, if not an agglomeration of shards and fragments blown in from other places and reconstituted to form a new whole, a new pattern? Marx practises a form of cartographic pointillism with his mosaic: the city is sharply in focus when viewed at distance, but pixilates into blur –as the city itself does – the closer we get to it.

3

Jules Verne serves Gerhard Marx well.When we look down at the earth from the window of an aeroplane it looks like a map of itself, just wierdly without the labels with which we have become familiar through applications such as Google Earth; a two-dimensional plane. Similarly, when Axel looks down at Copenhagen from the top of the Church of Our Saviour, he sees the “houses squashed flat” into the map-like formation that an aerial view brings. And yet we know that Professor Lidenbrock sees the earth’s surface not as a map, but as a skin, one he is planning to rupture as he drills down into the centre of the earth.

Paradoxically, by working with the two-dimensionality of maps, Marx compelsus to consider the specific verticality of his home-town. Johannesburg, of course, owes its very existence to the rupture of the earth’s surface. It’s vertical plane is described not only by the levels above its surface - its skyscrapers and its mine-dumps– but by those below, too: its gold mines. The two are directly related in an equation that defines Johannesburg’s development: the city rises above the plumbline of the earth’s surface in direct relation to the wealth that is dug out from beneath this surface.

Paradoxically, by working with the two-dimensionality of maps, Marx compelsus to consider the specific verticality of his home-town. Johannesburg, of course, owes its very existence to the rupture of the earth’s surface. It’s vertical plane is described not only by the levels above its surface - its skyscrapers and its mine-dumps– but by those below, too: its gold mines. The two are directly related in an equation that defines Johannesburg’s development: the city rises above the plumbline of the earth’s surface in direct relation to the wealth that is dug out from beneath this surface.

It is an equation that is unsustainable, economically, socially, and geologically: we build our bling ever higher on a void ever deeper, hoping that the flimsiest of tabs will hold it all together.

Marx’s artworks play with this instability. “Vertical Aerial” teeters on the axis of its crease. It is made off an aerial photograph shot earlyin the morning: the skyscrapers of downtown Johannesburg cast long shadows, which Marx and his team of mosaic-artists meticulously represent. The shadows present some kind of optical illusion, and seem to descend into the earth rather than to spill across it, suggesting the underground that we all know is there – but that, unless we are miners, we are able to ignore, as we skim along the surface of our hollow city.

And in “Garden Carpet”, pieces of plant material fall off the grid, dropping down into the obscure underworld beneath the city. This suggests not only humanity’s purposeful exploration of the planet but nature’s intrinsic quest for nourishment. Perhaps he did not intend it, but the glory of Gerhard Marx’s work in this exhibition turns on a pun that pulls human endeavour – not least his own – and natural impulse together: it is about rooting as much as it is about routing.

Marx’s artworks play with this instability. “Vertical Aerial” teeters on the axis of its crease. It is made off an aerial photograph shot earlyin the morning: the skyscrapers of downtown Johannesburg cast long shadows, which Marx and his team of mosaic-artists meticulously represent. The shadows present some kind of optical illusion, and seem to descend into the earth rather than to spill across it, suggesting the underground that we all know is there – but that, unless we are miners, we are able to ignore, as we skim along the surface of our hollow city.

And in “Garden Carpet”, pieces of plant material fall off the grid, dropping down into the obscure underworld beneath the city. This suggests not only humanity’s purposeful exploration of the planet but nature’s intrinsic quest for nourishment. Perhaps he did not intend it, but the glory of Gerhard Marx’s work in this exhibition turns on a pun that pulls human endeavour – not least his own – and natural impulse together: it is about rooting as much as it is about routing.

4