– Transparent Territory

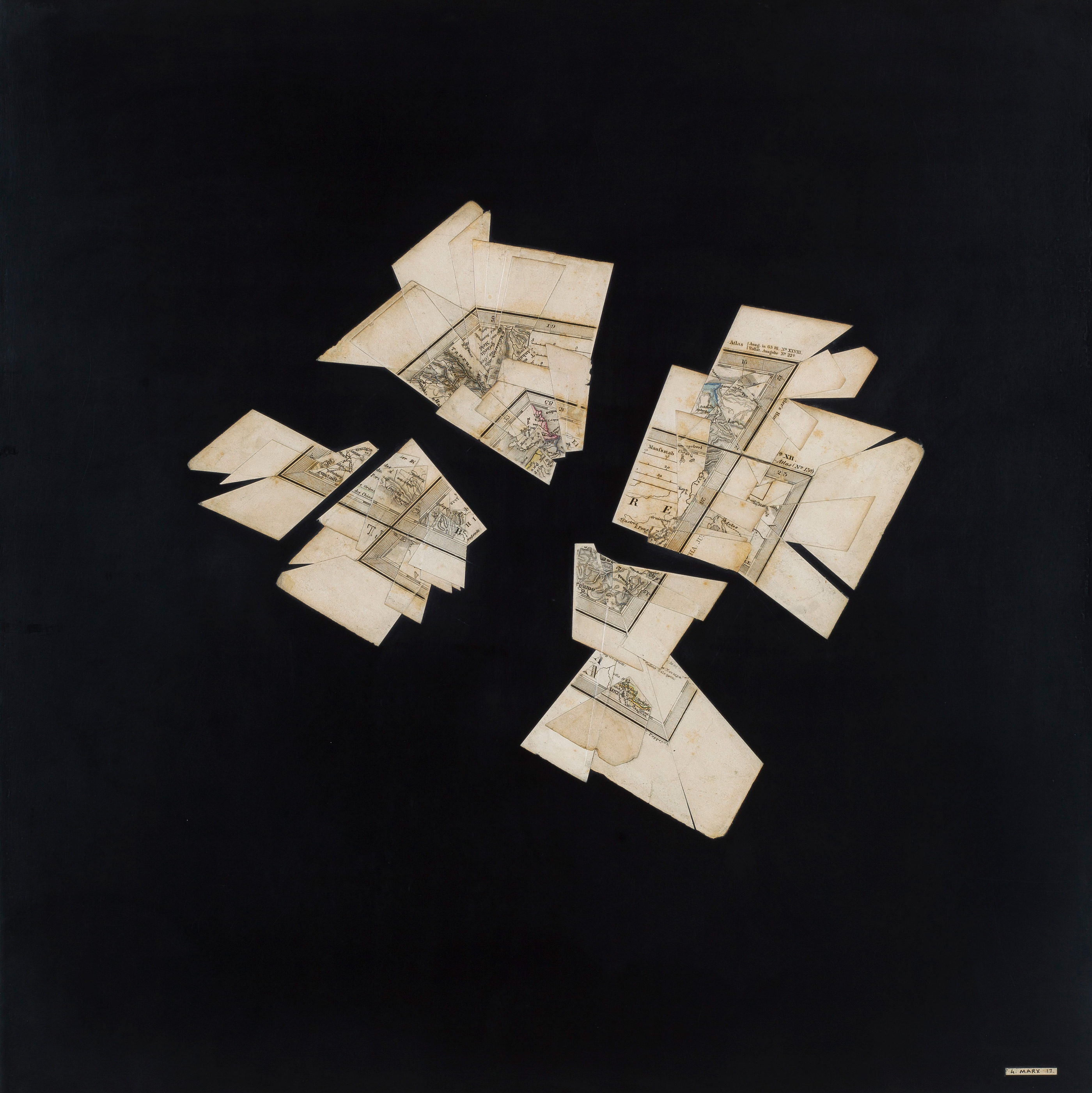

– Vehicle

– Calligraphy and Cartography

– Nearfar Object

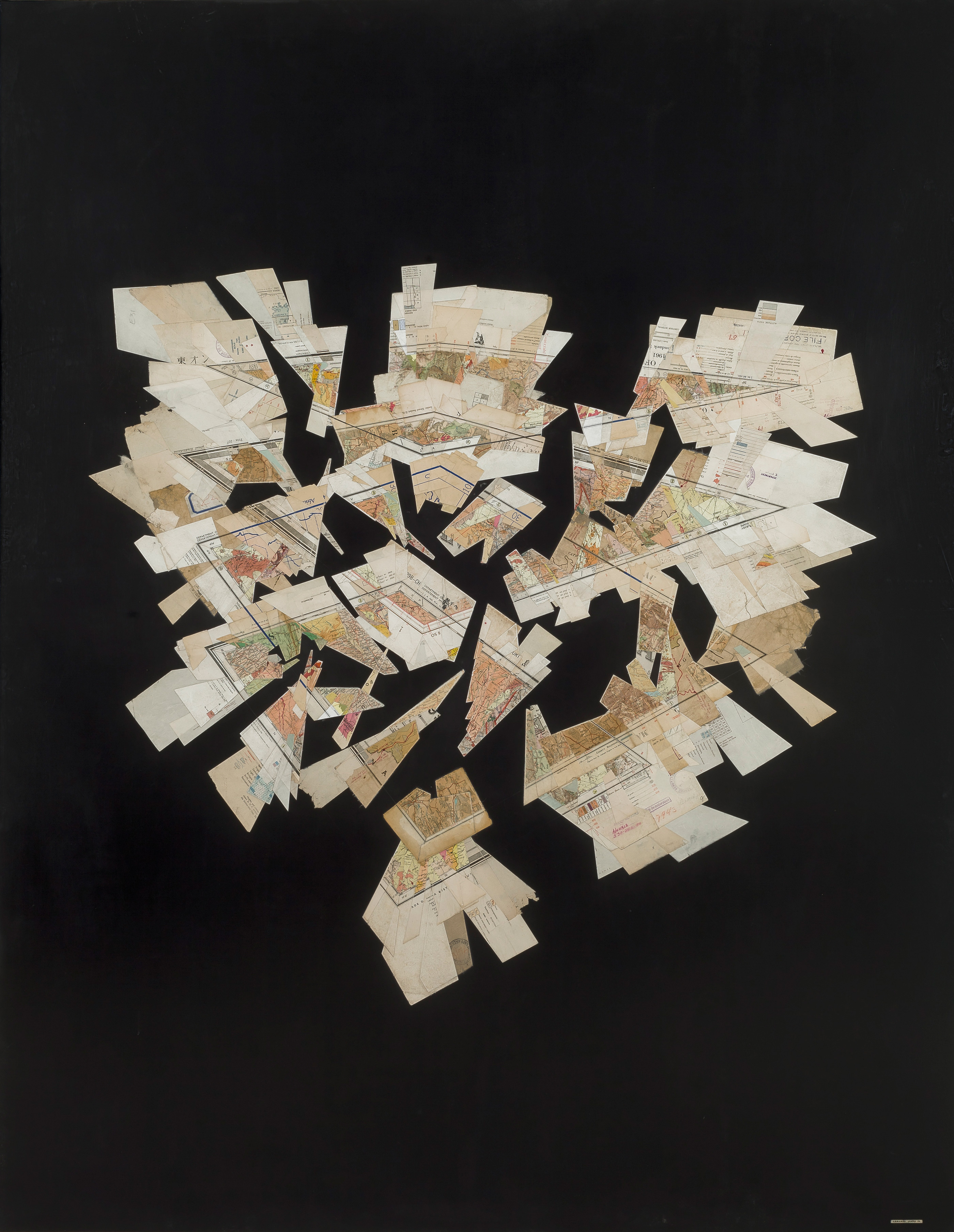

– Ecstatic Cartography

– Feral Map

– Vertical Aerial

– Agglomorate

– Depths in Feet

– Garden Carpet / Prayer Carpet

– Sculpture

– Vehicle

– Calligraphy and Cartography

– Nearfar Object

– Ecstatic Cartography

– Feral Map

– Vertical Aerial

– Agglomorate

– Depths in Feet

– Garden Carpet / Prayer Carpet

– Sculpture

FERAL TERRITORY

by Alexandra Dodd

Published to accompany Gerhard Marx’s exhibition:

Transparent Territories

Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg, 2017

Inspired by the artist’s method of constructing

original images from random map fragments, this text has been assembled from an

interview transcript and several email exchanges. Liberties have been taken

with the original texts. This composite dialogue bears some fidelity to the

communications as they initially transpired, but it has been reconstructed to

accentuate selected lines of inquiry.

GERHARD MARX: I made my

first map drawings in about 1999. At that point, the renaming of places was

happening at a broad scale in the country, so suddenly the map book that Maja

and I used to do road trips with became kind of irrelevant. You’d drive through

the country and the index to the landscape no longer applied – the semiotics in

relation to the landscape were shifting. I became aware of a disjuncture or

dissonance between the physical, phenomenological land and the way we read it

as landscape.

ALEXANDRA DODD: ‘Index’ feels like a useful word in relation to your work. I did a Thesaurus search and the words that appeared on my screen were: sign, indication, inventory, catalogue, register, directory, guide, indicator, gauge, measure, signal, mark, evidence, symptom, token, clue. ‘Indicator’ and ‘symptom’ appeal to me in relation to your tale of road-tripping through name-change territory. So yes, 1999 – what a number, what a year…

MARX: Around that same time, two of my grandparents were suffering from Alzheimer’s disease and a similar disjunction was happening with them. With Alzheimer’s, the person is still physically there, but their hold on language becomes unpredictable. When they subsequently passed away, things shifted again. Their physicality was lost and only memories remained. In making drawings of them using maps, I was literalising this experience – making a map while losing the person. The terrain would be lost, but the map would remain.

It was at that point that I first cut into the map that we used to travel with and it was quite a moment for me. I sat back and waited for the thunder to strike – it felt like a complete act of blasphemy or transgression. There is something about the absolute preciousness and authority of a map. The act of cutting into it still gives me a jolt.

DODD: So whether it is out of love or power, there is some sort of attachment for you to the authority of the intact map – it has a hold on you…

MARX: I grew up with a big reverence for these kind of visual languages. My father was an entomologist by training, and when I was very small, he would open his science books and I would copy the drawings in them while he was studying. That’s how I learnt to draw…

DODD: So there is the love.

MARX: But then there was this major upheaval for my generation. We came to realise that we had been misled. The map we had been given was seriously wrong – the way the world had been portrayed to us was a falsehood. Up to that moment of realisation the world had been portrayed in quite a utopian manner. There’s something of that nature in maps – they are beautiful, they veer towards the utopian, but they are flawed in their depictions of a singular world view. So there is love, but at the same time, an inherent distrust.

ALEXANDRA DODD: ‘Index’ feels like a useful word in relation to your work. I did a Thesaurus search and the words that appeared on my screen were: sign, indication, inventory, catalogue, register, directory, guide, indicator, gauge, measure, signal, mark, evidence, symptom, token, clue. ‘Indicator’ and ‘symptom’ appeal to me in relation to your tale of road-tripping through name-change territory. So yes, 1999 – what a number, what a year…

MARX: Around that same time, two of my grandparents were suffering from Alzheimer’s disease and a similar disjunction was happening with them. With Alzheimer’s, the person is still physically there, but their hold on language becomes unpredictable. When they subsequently passed away, things shifted again. Their physicality was lost and only memories remained. In making drawings of them using maps, I was literalising this experience – making a map while losing the person. The terrain would be lost, but the map would remain.

It was at that point that I first cut into the map that we used to travel with and it was quite a moment for me. I sat back and waited for the thunder to strike – it felt like a complete act of blasphemy or transgression. There is something about the absolute preciousness and authority of a map. The act of cutting into it still gives me a jolt.

DODD: So whether it is out of love or power, there is some sort of attachment for you to the authority of the intact map – it has a hold on you…

MARX: I grew up with a big reverence for these kind of visual languages. My father was an entomologist by training, and when I was very small, he would open his science books and I would copy the drawings in them while he was studying. That’s how I learnt to draw…

DODD: So there is the love.

MARX: But then there was this major upheaval for my generation. We came to realise that we had been misled. The map we had been given was seriously wrong – the way the world had been portrayed to us was a falsehood. Up to that moment of realisation the world had been portrayed in quite a utopian manner. There’s something of that nature in maps – they are beautiful, they veer towards the utopian, but they are flawed in their depictions of a singular world view. So there is love, but at the same time, an inherent distrust.

1

DODD: Yes, maps are flawed, they’re partial, but we

tend to treat them as objective truth. Cartography has played a huge role in

shaping how we think about the globe and our place on it, but map making has

always been subjective and provisional. For thousands of years, mystical lands

and religious ideas were labelled as actual places on maps and seemed just as

real to people as certain cities. When maps became implicated in the institutions

and processes of global modernity, they took on a scientific exactitude and

came to be seen as objective, absolute. But they have always been more about

representation than truthfulness. Maps are

flawed, but they’re also repositories of fascinating data. They are not simply

territorial, but a graphic way of representing particular sets of information.

MARX: A map is always a point of view and is always linked to a specific point in time. It always has an agenda. There is a reason for the map and the map depicts that reason. It doesn’t simply depict landscape; it is a way of looking at landscape.

DODD: I think this brings us closer to your current work.

MARX: Yes, I’ve worked with maps for almost two decades and my focus has been drawn to the frame. The frame contains the date, the scale, the compass, the index, the authorship and commissioning authority, the archival markings and the measurements of latitude and longitude. The frame also sits close to edge of the map and it’s the edges of the piece of paper that bear the markings of use and where the yellowing effects of time creep in. My current work uses the frame, the space left on the side for indexing and handling, and the edges of the paper. There’s always this framing device – the projection that captures and flattens the three-dimensional world. But it’s just that – a projection, a snapshot of a point of view really – not a truth. It’s a series of subjectivities that present themselves to you.

DODD: This calls to mind Simon Schama’s Landscape and Memory(New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1995). In that book he argued that landscape is a work of the mind, another compartment in the cultural baggage we all lug about. ‘There is a difference between land, which is earth, and landscape, which signifies a kind of jurisdiction. It always meant the framingof an image. The word originally came from the Dutch and had to do with making pictures.’

MARX: This is it. So my interest is in taking something that presents itself as objective truth and turning it into very subjective truth. I am speaking back to a particular kind of power by fragmenting it and turning into subjective utterance – a map of uncertainty.

DODD: Somehow I’m getting this picture of Donald Trump now… This fresh cultural panic about living in a ‘post-truth era’. Mostly, that thought tends to have a negative valence. We associate it with the phenomenon of fake news, miscommunication and the pliability of facts in the face of rogue politics. But for artists and writers, there’s always been something liberating in the ‘post-truth’ position. We could even think of it as a kind of triumph of post-modern theory – a dethroning of absolutism…

MARX: Yes. I’m interested in the lie, in the cheat – in refiguring the facts. I’m not using oil paint and moving from a space of formlessness towards something. I am using the material world and reshaping it. There’s this sense that this is the world that I was presented with, but what can I do with it, where can I go with it? I think the act of cutting the map breaks it out of its function. The moment I cut into it, it becomes an object – a terrain itself. It no longer refers to a terrain – it is a terrain. It becomes the object of scrutiny. So building up the surface, exploring the textural qualities of it, becomes a way of driving a wedge between the map and the terrain. It seems that the more I fragment the map, the more visible the signs of its fabrication become. And, almost ironically, the more pronounced the signs become, the more I become aware of the haunted and loaded space between them and the actual time and place they used to refer to.

DODD: How self-reflexive do you want be in relation to the very real politics of land in South Africa at the moment?

MARX: I am interested in how land functions in relation to identity, our need to belong. This is central to a range of social and political concerns, from utopian notions attached to ideas of belonging to the more dystopian, almost apocalyptic scenarios that underlie ecological projections.

On a very basic level, a lot of these works are about being a father and trying to imagine a space for my children in the world – whether it’s the project of making a house or providing shelter. It builds outwards from there. Some of the works in the Ecstatic Maps series were made after the recent death of my father. There’s all this psychology and emotion without an anchor to the physical. It’s from this this non-place that I’m interested in the notion of deterritorialisation. The ‘trans-parent’ in Transparent Territory alludes to a space beyond the parent – beyond heritage, in as much as that is ever possible.

DODD: To some extent, these map drawings call to mind mounting tensions within South Africa in relation to the land – the pain of dispossession, rage due to the slow pace of redistribution, anxiety around the threat of violent land grabs – all bound up in a shifting network of inherited lines and limits that divide the land into territory, domain and jurisdiction. Is that something you’re conscious about?

MARX: Yes. The question of land is essential to these works, but I wouldn’t want to frame them solely in terms South African politics. The Transparent Territory works are not only constituted of South African maps – although they all circulated in South Africa. They are random amalgamations of fragments of Europe, America, Africa, China – whatever arrives on the cutting board. In piecing them together I’m conflating space and historical time (some are recent maps, whereas some date back to the early 20th century) into what I think of as ‘migrant maps’.

The colonial project itself was and continues to be an extreme act of fragmentation and grafting. Much of our current lives is a direct result of those ruptures and our present moment is equally fragmented. The radio is playing in the background as I work and I hear that America bombed Syria today. And there is a map of Damascus lying here. Suddenly in comes Slovenia, in comes Hungary, Romania, Germany – and suddenly all the pointers to my wife’s family are there – all the disruption in Europe that marked life there and eventually brought our families here. It’s that kind of arbitrariness that brings us to a place.

Some of the works look directly at ‘the raft’, as witnessed in the current migration crises, as a man-made island of sorts – unfixed, floating, temporal, usually of a hybridized nature, a desperate fabrication of a foothold in the space between land(s). I like to think of my maps as something quite similar.

MARX: A map is always a point of view and is always linked to a specific point in time. It always has an agenda. There is a reason for the map and the map depicts that reason. It doesn’t simply depict landscape; it is a way of looking at landscape.

DODD: I think this brings us closer to your current work.

MARX: Yes, I’ve worked with maps for almost two decades and my focus has been drawn to the frame. The frame contains the date, the scale, the compass, the index, the authorship and commissioning authority, the archival markings and the measurements of latitude and longitude. The frame also sits close to edge of the map and it’s the edges of the piece of paper that bear the markings of use and where the yellowing effects of time creep in. My current work uses the frame, the space left on the side for indexing and handling, and the edges of the paper. There’s always this framing device – the projection that captures and flattens the three-dimensional world. But it’s just that – a projection, a snapshot of a point of view really – not a truth. It’s a series of subjectivities that present themselves to you.

DODD: This calls to mind Simon Schama’s Landscape and Memory(New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1995). In that book he argued that landscape is a work of the mind, another compartment in the cultural baggage we all lug about. ‘There is a difference between land, which is earth, and landscape, which signifies a kind of jurisdiction. It always meant the framingof an image. The word originally came from the Dutch and had to do with making pictures.’

MARX: This is it. So my interest is in taking something that presents itself as objective truth and turning it into very subjective truth. I am speaking back to a particular kind of power by fragmenting it and turning into subjective utterance – a map of uncertainty.

DODD: Somehow I’m getting this picture of Donald Trump now… This fresh cultural panic about living in a ‘post-truth era’. Mostly, that thought tends to have a negative valence. We associate it with the phenomenon of fake news, miscommunication and the pliability of facts in the face of rogue politics. But for artists and writers, there’s always been something liberating in the ‘post-truth’ position. We could even think of it as a kind of triumph of post-modern theory – a dethroning of absolutism…

MARX: Yes. I’m interested in the lie, in the cheat – in refiguring the facts. I’m not using oil paint and moving from a space of formlessness towards something. I am using the material world and reshaping it. There’s this sense that this is the world that I was presented with, but what can I do with it, where can I go with it? I think the act of cutting the map breaks it out of its function. The moment I cut into it, it becomes an object – a terrain itself. It no longer refers to a terrain – it is a terrain. It becomes the object of scrutiny. So building up the surface, exploring the textural qualities of it, becomes a way of driving a wedge between the map and the terrain. It seems that the more I fragment the map, the more visible the signs of its fabrication become. And, almost ironically, the more pronounced the signs become, the more I become aware of the haunted and loaded space between them and the actual time and place they used to refer to.

DODD: How self-reflexive do you want be in relation to the very real politics of land in South Africa at the moment?

MARX: I am interested in how land functions in relation to identity, our need to belong. This is central to a range of social and political concerns, from utopian notions attached to ideas of belonging to the more dystopian, almost apocalyptic scenarios that underlie ecological projections.

On a very basic level, a lot of these works are about being a father and trying to imagine a space for my children in the world – whether it’s the project of making a house or providing shelter. It builds outwards from there. Some of the works in the Ecstatic Maps series were made after the recent death of my father. There’s all this psychology and emotion without an anchor to the physical. It’s from this this non-place that I’m interested in the notion of deterritorialisation. The ‘trans-parent’ in Transparent Territory alludes to a space beyond the parent – beyond heritage, in as much as that is ever possible.

DODD: To some extent, these map drawings call to mind mounting tensions within South Africa in relation to the land – the pain of dispossession, rage due to the slow pace of redistribution, anxiety around the threat of violent land grabs – all bound up in a shifting network of inherited lines and limits that divide the land into territory, domain and jurisdiction. Is that something you’re conscious about?

MARX: Yes. The question of land is essential to these works, but I wouldn’t want to frame them solely in terms South African politics. The Transparent Territory works are not only constituted of South African maps – although they all circulated in South Africa. They are random amalgamations of fragments of Europe, America, Africa, China – whatever arrives on the cutting board. In piecing them together I’m conflating space and historical time (some are recent maps, whereas some date back to the early 20th century) into what I think of as ‘migrant maps’.

The colonial project itself was and continues to be an extreme act of fragmentation and grafting. Much of our current lives is a direct result of those ruptures and our present moment is equally fragmented. The radio is playing in the background as I work and I hear that America bombed Syria today. And there is a map of Damascus lying here. Suddenly in comes Slovenia, in comes Hungary, Romania, Germany – and suddenly all the pointers to my wife’s family are there – all the disruption in Europe that marked life there and eventually brought our families here. It’s that kind of arbitrariness that brings us to a place.

Some of the works look directly at ‘the raft’, as witnessed in the current migration crises, as a man-made island of sorts – unfixed, floating, temporal, usually of a hybridized nature, a desperate fabrication of a foothold in the space between land(s). I like to think of my maps as something quite similar.

2

DODD: You’ve spoken about making these works as a kind

of performance. Can we speak about the process?

MARX: Well, firstly let’s talk about where they come from. I never go out and buy maps; I wait for them to come to me – and somehow they do. I have a huge pile of maps in my garage. It takes two people a full day to move them. It’s the sheer weight of paper. A map in itself is a flimsy thing that speaks to mobility and travel and folding it up and putting it in your pocket. But a pile of maps is a heavy burden.

I’ll get a call from someone and they’ll say: ‘I’m sitting with a pile of maps that belonged to my grandmother. Somehow they ended up with me and they’re taking up a lot of space. I don’t know what to do with them. I need to get rid of them, but they’re records of all her travels – I can’t just throw them away. Basically, what they’re saying is: ‘I’m stuck with the objecthood of my nostalgia.’

DODD: So there’s a strange, magic hold within them because just destroying them is not an option. For better or for worse, people can’t bring themselves to kill off the past so completely.

MARX: Yes, there’s this sense of: ‘I know that these maps meant something to my grandmother, but I don’t actually know what they mean; I wasn’t part of that journey.’

DODD: So the attachment is emotional and subjective rather than cerebral. The maps are no longer understood, but they have an aura of value – a strange grip. They are taking up space, but they are not junk. People can’t just throw them in the trash. There’s this hope for some kind of trans-generational transmission.

MARX: Yes, there’s that. But I might also get a call from a friend at a library/archive/institution saying: ‘There’s this pile of decommissioned maps, but if you want them, you’ve got to come immediately.’ And basically, what he’s saying is: ‘Do you want to come and save them before they get pulped? They might still have some life in them’.

I’ll go there, park my car, and literally spend two days carrying out piles of maps with my own two arms. And the strangest thing is that, when you’re carrying piles of them, they have this limpness; they feel like bodies. Such crazy Derridean moments. It’s a bit like someone phoning the snake handler. Or when you’ve got bees on your property; who are you going to call? ‘I’ve got maps lying around; phone Gerhard – he’ll destroy them elegantly.’

DODD: Amazing that you mention Derrida – for Derrida the fever in Archive Fever always arises out of a future-bound imperative. And in a sense that’s exactly what these abandoned maps are getting when they come into your custody; some kind of hold on the future.

MARX: Yes, in some sense, I am rescuing the maps and giving them a second life. Maps want to be somewhat outside of time, but they do age, both literally and in terms of viewpoint. So I try to capture the yellowing and the foxing in the works. At the same time, I’m obliterating the original iteration. Part of the pull of these works is this tension between destruction and the act of drawing.

DODD: Perhaps they were never intended to endure across all time. Maybe they were intended as fleeting, ephemeral objects in the first place – impressionable and impressionistic.

MARX: A map speaks to truth, but it isn’t truth. It speaks to historical time, but has a very fleeting foothold in that matrix. It’s the record of an attempt at seeing or visualising something. It’s never more than an attempt.

DODD: So these maps have been decommissioned from the archive?

MARX: That’s right – the archive does not want them. Either they’re doubles, or shifts in curatorial focus have rendered them irrelevant or unwanted. Also, to a large extent, the map as a physical printed object has become redundant in the move to digital archiving.

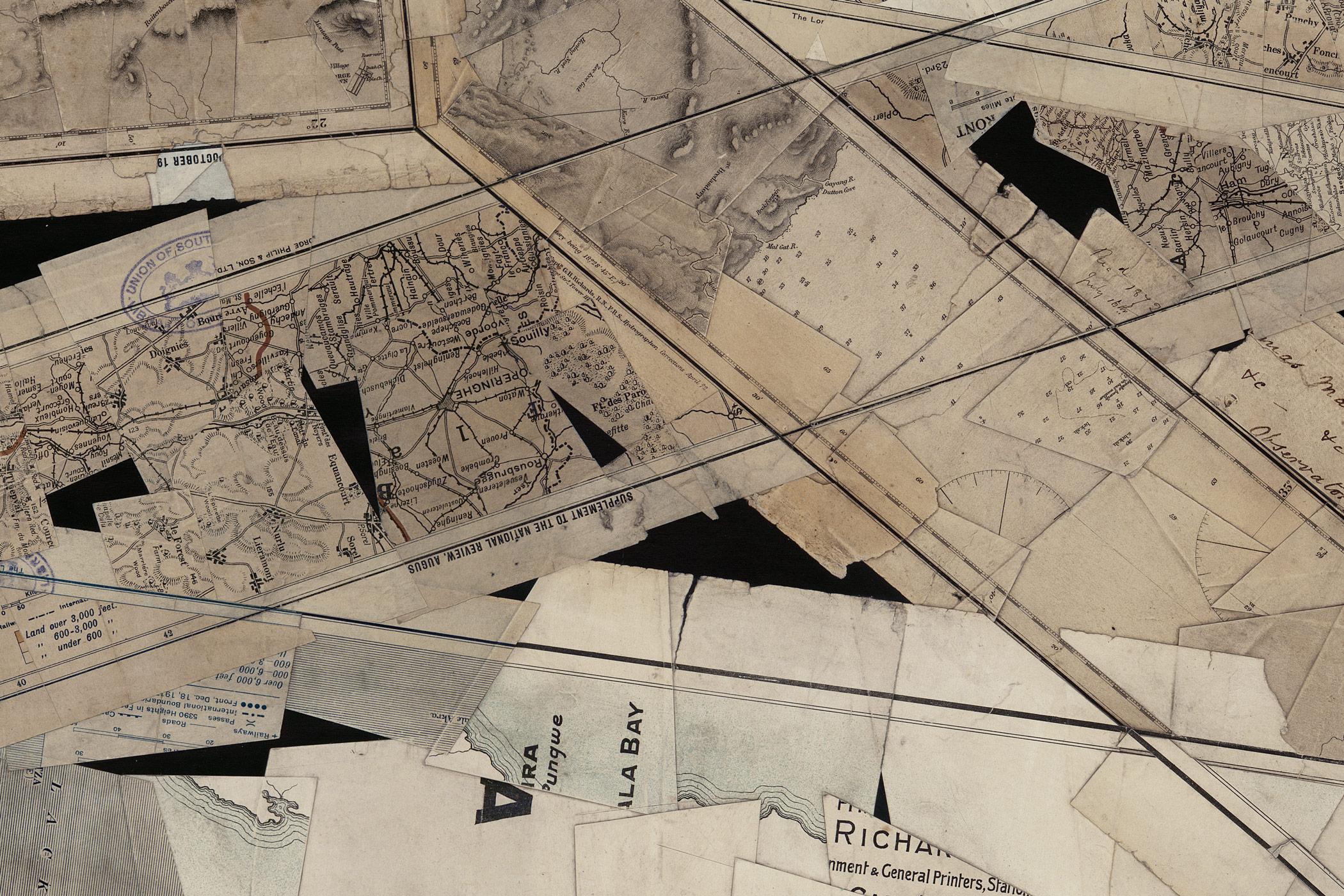

DODD: I appreciate the inclusion of the institutional relics – fragments of old bureaucratic stamps that give fleeting clues of the maps’ provenance within ordained structures of knowledge and power. They hint at the fact that there was always a certain kind of institutional power behind these now-deconstructed versions of the world.

MARX: Here’s the Italian Campaign (from the Union of South Africa Library of Parliament). It was published in May 1916 and then it’s got another stamp that says January 1938 and an accession number. What’s beautiful is that these maps were clearly studied and if you lift them to the light, you can see the pinholes where people pinned them. Somebody touched them at some point. They served a function. Now they’re just tatters of yellow paper.

DODD: Now deemed irrelevant, meaningless, toxic or too cumbersome to store and protect for posterity, they are being discarded from institutional strongholds. There are limits to what any archive can hold or preserve – only two of each animal on Noah’s ark… These maps no longer conform to the mandate. Their import for futurity has somehow dissipated.

MARX: This reminds me of the earlier plant drawings I did when I lived in Joburg. I was always pillaging… I was interested in the idea of the gardener as a kind of curator. So the garden rubble was what the curator didn’t want – it was the beast that was expelled from the garden, little bits of wilderness in a highly regulated landscape. In Johannesburg, you’d find these piles of rubble on pedestrian sidewalks, and I would rummage through people’s discarded garden refuse to find the lines and bends for my own structures. The discarded, grafting, hybridity – that kind of thing runs through all my work.

DODD: Yes, I see that – that seeking out of the winding, rhizomatic, uncontrollable nature of knowledge rather than the systematic grid-like aspect of knowledge as control…

MARX: There’s the logic of collecting and then there’s the process in which a different logic emerges through grafting and rearrangement. I prefer to pursue an intrigue, a ‘hunch’ – otherwise I’m just sticking pieces of paper down. Even if I’m looking for a particular line thickness or colour range there must always be a pursuit. From this practical process the conceptual and philosophical narratives grow. This is maybe what makes me more of a sculptor than a painter – as long as I can construct a logic, I can keep making.

DODD: At what point in the making process does the logic emerge for you?

MARX: It is almost immediate, but it might shift over time. I start and follow the line, and once I’ve got five fragments, the logic begins to emerge. I disregard the content of the map and just look at it visually. It’s a process of thinking as you make and making as you think – a very lively project of doing something and then trying to understand what the fact of you doing it means. It’s definitely not expressionistic. It’s an investigative project that I set in motion and that I then have to solve. I don’t make work to express myself, but because I’m interested in things – want to engage with things. The act of making is an act of embodied thinking for me – a way of thinking with my hands.

DODD: So it’s a research-based form of practice – driven by the question?

MARX: It’s a process of engagement and dialogue with different maps or materials bringing different qualities. As I work with a particular maps I open a language and the language tells me what its poetics and possibilities are.

MARX: Well, firstly let’s talk about where they come from. I never go out and buy maps; I wait for them to come to me – and somehow they do. I have a huge pile of maps in my garage. It takes two people a full day to move them. It’s the sheer weight of paper. A map in itself is a flimsy thing that speaks to mobility and travel and folding it up and putting it in your pocket. But a pile of maps is a heavy burden.

I’ll get a call from someone and they’ll say: ‘I’m sitting with a pile of maps that belonged to my grandmother. Somehow they ended up with me and they’re taking up a lot of space. I don’t know what to do with them. I need to get rid of them, but they’re records of all her travels – I can’t just throw them away. Basically, what they’re saying is: ‘I’m stuck with the objecthood of my nostalgia.’

DODD: So there’s a strange, magic hold within them because just destroying them is not an option. For better or for worse, people can’t bring themselves to kill off the past so completely.

MARX: Yes, there’s this sense of: ‘I know that these maps meant something to my grandmother, but I don’t actually know what they mean; I wasn’t part of that journey.’

DODD: So the attachment is emotional and subjective rather than cerebral. The maps are no longer understood, but they have an aura of value – a strange grip. They are taking up space, but they are not junk. People can’t just throw them in the trash. There’s this hope for some kind of trans-generational transmission.

MARX: Yes, there’s that. But I might also get a call from a friend at a library/archive/institution saying: ‘There’s this pile of decommissioned maps, but if you want them, you’ve got to come immediately.’ And basically, what he’s saying is: ‘Do you want to come and save them before they get pulped? They might still have some life in them’.

I’ll go there, park my car, and literally spend two days carrying out piles of maps with my own two arms. And the strangest thing is that, when you’re carrying piles of them, they have this limpness; they feel like bodies. Such crazy Derridean moments. It’s a bit like someone phoning the snake handler. Or when you’ve got bees on your property; who are you going to call? ‘I’ve got maps lying around; phone Gerhard – he’ll destroy them elegantly.’

DODD: Amazing that you mention Derrida – for Derrida the fever in Archive Fever always arises out of a future-bound imperative. And in a sense that’s exactly what these abandoned maps are getting when they come into your custody; some kind of hold on the future.

MARX: Yes, in some sense, I am rescuing the maps and giving them a second life. Maps want to be somewhat outside of time, but they do age, both literally and in terms of viewpoint. So I try to capture the yellowing and the foxing in the works. At the same time, I’m obliterating the original iteration. Part of the pull of these works is this tension between destruction and the act of drawing.

DODD: Perhaps they were never intended to endure across all time. Maybe they were intended as fleeting, ephemeral objects in the first place – impressionable and impressionistic.

MARX: A map speaks to truth, but it isn’t truth. It speaks to historical time, but has a very fleeting foothold in that matrix. It’s the record of an attempt at seeing or visualising something. It’s never more than an attempt.

DODD: So these maps have been decommissioned from the archive?

MARX: That’s right – the archive does not want them. Either they’re doubles, or shifts in curatorial focus have rendered them irrelevant or unwanted. Also, to a large extent, the map as a physical printed object has become redundant in the move to digital archiving.

DODD: I appreciate the inclusion of the institutional relics – fragments of old bureaucratic stamps that give fleeting clues of the maps’ provenance within ordained structures of knowledge and power. They hint at the fact that there was always a certain kind of institutional power behind these now-deconstructed versions of the world.

MARX: Here’s the Italian Campaign (from the Union of South Africa Library of Parliament). It was published in May 1916 and then it’s got another stamp that says January 1938 and an accession number. What’s beautiful is that these maps were clearly studied and if you lift them to the light, you can see the pinholes where people pinned them. Somebody touched them at some point. They served a function. Now they’re just tatters of yellow paper.

DODD: Now deemed irrelevant, meaningless, toxic or too cumbersome to store and protect for posterity, they are being discarded from institutional strongholds. There are limits to what any archive can hold or preserve – only two of each animal on Noah’s ark… These maps no longer conform to the mandate. Their import for futurity has somehow dissipated.

MARX: This reminds me of the earlier plant drawings I did when I lived in Joburg. I was always pillaging… I was interested in the idea of the gardener as a kind of curator. So the garden rubble was what the curator didn’t want – it was the beast that was expelled from the garden, little bits of wilderness in a highly regulated landscape. In Johannesburg, you’d find these piles of rubble on pedestrian sidewalks, and I would rummage through people’s discarded garden refuse to find the lines and bends for my own structures. The discarded, grafting, hybridity – that kind of thing runs through all my work.

DODD: Yes, I see that – that seeking out of the winding, rhizomatic, uncontrollable nature of knowledge rather than the systematic grid-like aspect of knowledge as control…

MARX: There’s the logic of collecting and then there’s the process in which a different logic emerges through grafting and rearrangement. I prefer to pursue an intrigue, a ‘hunch’ – otherwise I’m just sticking pieces of paper down. Even if I’m looking for a particular line thickness or colour range there must always be a pursuit. From this practical process the conceptual and philosophical narratives grow. This is maybe what makes me more of a sculptor than a painter – as long as I can construct a logic, I can keep making.

DODD: At what point in the making process does the logic emerge for you?

MARX: It is almost immediate, but it might shift over time. I start and follow the line, and once I’ve got five fragments, the logic begins to emerge. I disregard the content of the map and just look at it visually. It’s a process of thinking as you make and making as you think – a very lively project of doing something and then trying to understand what the fact of you doing it means. It’s definitely not expressionistic. It’s an investigative project that I set in motion and that I then have to solve. I don’t make work to express myself, but because I’m interested in things – want to engage with things. The act of making is an act of embodied thinking for me – a way of thinking with my hands.

DODD: So it’s a research-based form of practice – driven by the question?

MARX: It’s a process of engagement and dialogue with different maps or materials bringing different qualities. As I work with a particular maps I open a language and the language tells me what its poetics and possibilities are.

3

DODD: So what logics guided the making of the Transparent Territories series?

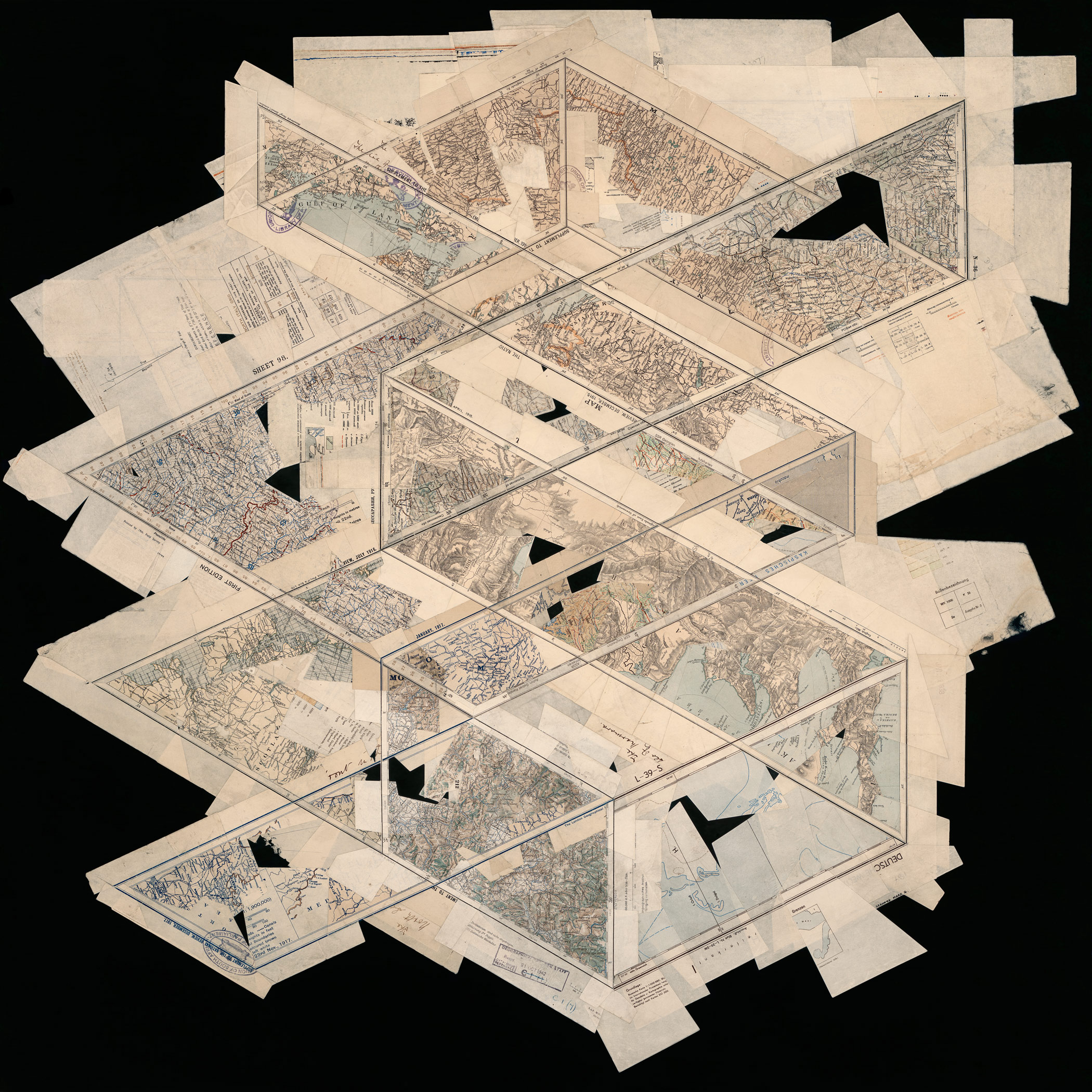

MARX: This series grew out of my Depths in Feetseries and my interest in the idea of the frame and the map as a projection. I realised that I could undermine the map’s solidity by making the maps appear transparent – as if you can see one map through another and read them more like lenses, sheets of glass, or filters. Various spatial propositions emerge as the flatness of the map opens up into architectural geometries suggested through overlaying, folding and intersection.

I have always been intrigued by the architectural backgrounds in Giotto’s paintings – they sit like strange, crystal-like geometries in parallel to the human dramas he depicts, ascribing to a different sense of perspective. I printed out a series of these paintings and blocked out the human figures with thick black tape to remove the anthropocentrism from the images. These references became central. I like to think that these works ‘flicker’ between the suggested dimensionality of the maps and their inherent flatness. The maps started to suggest spaces one might enter, like a chamber or an excavation site.

In some of the more recent Transparent Territory works, only small fragments of line describe the shapes of the planes in space. I try to give as little information as possible. I only draw the corners, the seams, the intersections, and the elements that are essential to describe the dimensionality of the geometries. They are fragments built from fragments and they float like jetsam in space.

DODD: Sometimes there is a sense of explosion or scattering.

MARX: But that incoherence is offset by the need to find a narrative, a relationship between the parts. The sense of perspective conveyed by the shapes I build contradicts the perspectivelessness of a map. The original map is meant from a God’s eye view where you look directly down and there’s no perspective. But shifting it to a 45º-ish angle, I’m emphasising the map in space – the map as an object in the world, a physical terrain in itself. So suddenly there’s this spatial dimension, it becomes something of a still life.

DODD: Why 45º particularly?

MARX: Well, if you’re at a 0º angle you are in the landscape – the perspective of landscape drawing or painting. At 90º, you are at a remove from the landscape. This is the aerial perspective – the god’s-eye view. It has a particular relationship of power to the landscape. The 45º viewpoint sits somewhere in between, as if you’re on a mountain. You’re at remove, but you’re still in the landscape. I’m interested in pushing the map to this intermediate 45º perspective where landscape almost becomes map and map starts to become landscape.

DODD: How do you achieve that?

MARX: On a practical level, by severing the 90º angles and reassembling them, I’m forcing the map into perspective – turning the map into a territory.

Also, there’s a cartographic practice in which landscape drawings are used to decipher the aerial view. The landscape drawings are included into the map like a key, and describe various landmarks that you would see as you move around the coast. So the reader of the map would presumably be at sea and would need to recognise features in the landscape in order to locate themselves on the map. I love the idea of a cartographer on uncertain ground or no on ground at all. There are all these shifting points and there’s a sense of a raft, or a sense of being at sea. You’re trying to locate yourself and your position in terms of the landscape, but the landscape is shifting, you’re shifting, so there’s a beautiful futility to the process of map-making in the face of that. It’s a Memento Mori of sorts if you look at it like this.

DODD: As someone who suffers from vertigo, I find that the effect is slightly induced by these works. I have a sense of being constantly shifted.

MARX: Yes, vertigo – that sense of groundlessness or uncertainty of ground – is central to these works. My previous exhibition with Goodman, Johannesburg was entitled ‘Lessons In Looking Down’. It referred to Jules Verne’s characters from Journey to the Centre of the Earth, who practise running down high staircases, looking down, in order to overcome their sense of vertigo before they descend into the earth. More and more geological maps have entered my work recently, mappings of the subterranean landscape. Even subterranean space feels like it has been mapped, mined, fracked and exploited; it is not the solid ground it once was. In a way I am mapping the landslide.

DODD: I love the utopian thrust in the title ‘Ecstatic Cartography’ and the feeling that these reshaped maps are individual acts of liberation from a kind of conceptual entrapment.

MARX: The irony is that a map is by definition an ecstatic object. The root of the word ‘ecstasy’ is in the Ancient Greek word ‘ekstasis’, which means ‘to be or stand outside oneself, a removal to elsewhere’. In order to have an aerial view of your position, you need to stand outside of your body, so a map is implicitly an ecstatic object. It’s always ecstatic. In reading it, you always imagine yourself to be where you are not.

DODD: There is also an ecstatic exchange between the viewer and the work. The combination of shape, energy and colour seems to offer up some abstract prospect – an opportunity to navigate an unknown space that you might wish to explore further.

MARX: I’ve been pushing the maps into a painterly space where it’s a very visceral experience looking at them. They are all about colour and line and mark-making – graphic qualities. If this was traditional painting, you might look at it and respond on an emotional, subjective level, but with a map you tend to read yourself into the image in terms of positionality and points of recognition. Even when they’re fragmented like this, you tend to try and find yourself in them.

DODD: I suppose, for those initiated into the language of mapping, there will always be that instinctual pull to locate themselves within the territory. As someone who has resisted the absolute logic of maps for most of my life, preferring to get lost or ask for directions, I lack that impulse and respond more to the abstraction of the new shapes you’ve forged and to that sci-fi sense of dimensionless black space.

MARX: The black surfaces actually come from trying to draw with plant material. I was looking at herbariums and a collection of plants. I wanted to draw with the natural lines that pressed plants offer, so I was looking at how plants are pressed. Botanists stick them down with little strips of paper, in order to loosen them again in time. The only way I could find to stick them down was to apply glue to the surface, which was ugly. Then in time I realised that if the glue spreads across the whole canvas, the entire surface is adhesive. So I prepare the canvas with a mixture of wood glue and paint, and in the making stage it’s a very lively adhesive surface that I can attach stuff to. Afterwards I polish it so that the surface can’t get easily affected by water or mist. I apply layer after layer, so it’s a slow process of applying, then sanding, applying, then sanding. And the blackness has that tar-like, bitumen quality, which makes me think of the bog bodies in Ireland – human bodies mummified in peat.

DODD: Yes, there’s that ancient peaty earth aspect – Seamus Heaney’s Tollund Man. But it’s also the sci-fi blackness of outer space that is conjured.

MARX: I’ve always thought that there are two neutralities or voids in making work. The white void is the gallery, which is the space in which there is nothing until there’s something. The black void is the void of theatre, in which I’ve worked extensively. And in the theatrical space, everything is there and gets revealed through light and narrative. So everything is already present and comes to light as it gains significance. It’s like history. What I love about these maps is that I’m speaking into this vast history where everything is already there, but I’m threading the fragments into a kind of a narrative. That’s how I think about the blackness.

DODD: And then there are the hovering shapes against the plain of blackness. They strike me as being very architectural structures – or exercises in a kind of impossible architecture. There’s that mise en abyme sense of infinite recursion – an interior within an interior within an interior…

MARX: In map convention the ‘interior within an interior’ logic speaks to the tradition of a ‘key’ – the smaller map informs the larger. In these works they inform, contradict, layer, even intersect each other. Most of my work stems from an interest in indexical objects – self effacing objects that point elsewhere. A map doesn’t point to itself; it is a guide to a broader landscape beyond itself, so in theory, changing the map changes the way we depict and know the world.

In making these maps, I’m asking myself: If maps aim to represent something complex through simplification, does it follow that complicating the map could complicate the terrain? If I can somehow complicate a map’s flatness, does it start to hint at a more complex dimensional world view? Does complicating the flat sheet – the Mappa Mundi – imply a re-wilding of sorts, returning ‘territory’ to wilderness?

_MARX: This series grew out of my Depths in Feetseries and my interest in the idea of the frame and the map as a projection. I realised that I could undermine the map’s solidity by making the maps appear transparent – as if you can see one map through another and read them more like lenses, sheets of glass, or filters. Various spatial propositions emerge as the flatness of the map opens up into architectural geometries suggested through overlaying, folding and intersection.

I have always been intrigued by the architectural backgrounds in Giotto’s paintings – they sit like strange, crystal-like geometries in parallel to the human dramas he depicts, ascribing to a different sense of perspective. I printed out a series of these paintings and blocked out the human figures with thick black tape to remove the anthropocentrism from the images. These references became central. I like to think that these works ‘flicker’ between the suggested dimensionality of the maps and their inherent flatness. The maps started to suggest spaces one might enter, like a chamber or an excavation site.

In some of the more recent Transparent Territory works, only small fragments of line describe the shapes of the planes in space. I try to give as little information as possible. I only draw the corners, the seams, the intersections, and the elements that are essential to describe the dimensionality of the geometries. They are fragments built from fragments and they float like jetsam in space.

DODD: Sometimes there is a sense of explosion or scattering.

MARX: But that incoherence is offset by the need to find a narrative, a relationship between the parts. The sense of perspective conveyed by the shapes I build contradicts the perspectivelessness of a map. The original map is meant from a God’s eye view where you look directly down and there’s no perspective. But shifting it to a 45º-ish angle, I’m emphasising the map in space – the map as an object in the world, a physical terrain in itself. So suddenly there’s this spatial dimension, it becomes something of a still life.

DODD: Why 45º particularly?

MARX: Well, if you’re at a 0º angle you are in the landscape – the perspective of landscape drawing or painting. At 90º, you are at a remove from the landscape. This is the aerial perspective – the god’s-eye view. It has a particular relationship of power to the landscape. The 45º viewpoint sits somewhere in between, as if you’re on a mountain. You’re at remove, but you’re still in the landscape. I’m interested in pushing the map to this intermediate 45º perspective where landscape almost becomes map and map starts to become landscape.

DODD: How do you achieve that?

MARX: On a practical level, by severing the 90º angles and reassembling them, I’m forcing the map into perspective – turning the map into a territory.

Also, there’s a cartographic practice in which landscape drawings are used to decipher the aerial view. The landscape drawings are included into the map like a key, and describe various landmarks that you would see as you move around the coast. So the reader of the map would presumably be at sea and would need to recognise features in the landscape in order to locate themselves on the map. I love the idea of a cartographer on uncertain ground or no on ground at all. There are all these shifting points and there’s a sense of a raft, or a sense of being at sea. You’re trying to locate yourself and your position in terms of the landscape, but the landscape is shifting, you’re shifting, so there’s a beautiful futility to the process of map-making in the face of that. It’s a Memento Mori of sorts if you look at it like this.

DODD: As someone who suffers from vertigo, I find that the effect is slightly induced by these works. I have a sense of being constantly shifted.

MARX: Yes, vertigo – that sense of groundlessness or uncertainty of ground – is central to these works. My previous exhibition with Goodman, Johannesburg was entitled ‘Lessons In Looking Down’. It referred to Jules Verne’s characters from Journey to the Centre of the Earth, who practise running down high staircases, looking down, in order to overcome their sense of vertigo before they descend into the earth. More and more geological maps have entered my work recently, mappings of the subterranean landscape. Even subterranean space feels like it has been mapped, mined, fracked and exploited; it is not the solid ground it once was. In a way I am mapping the landslide.

DODD: I love the utopian thrust in the title ‘Ecstatic Cartography’ and the feeling that these reshaped maps are individual acts of liberation from a kind of conceptual entrapment.

MARX: The irony is that a map is by definition an ecstatic object. The root of the word ‘ecstasy’ is in the Ancient Greek word ‘ekstasis’, which means ‘to be or stand outside oneself, a removal to elsewhere’. In order to have an aerial view of your position, you need to stand outside of your body, so a map is implicitly an ecstatic object. It’s always ecstatic. In reading it, you always imagine yourself to be where you are not.

DODD: There is also an ecstatic exchange between the viewer and the work. The combination of shape, energy and colour seems to offer up some abstract prospect – an opportunity to navigate an unknown space that you might wish to explore further.

MARX: I’ve been pushing the maps into a painterly space where it’s a very visceral experience looking at them. They are all about colour and line and mark-making – graphic qualities. If this was traditional painting, you might look at it and respond on an emotional, subjective level, but with a map you tend to read yourself into the image in terms of positionality and points of recognition. Even when they’re fragmented like this, you tend to try and find yourself in them.

DODD: I suppose, for those initiated into the language of mapping, there will always be that instinctual pull to locate themselves within the territory. As someone who has resisted the absolute logic of maps for most of my life, preferring to get lost or ask for directions, I lack that impulse and respond more to the abstraction of the new shapes you’ve forged and to that sci-fi sense of dimensionless black space.

MARX: The black surfaces actually come from trying to draw with plant material. I was looking at herbariums and a collection of plants. I wanted to draw with the natural lines that pressed plants offer, so I was looking at how plants are pressed. Botanists stick them down with little strips of paper, in order to loosen them again in time. The only way I could find to stick them down was to apply glue to the surface, which was ugly. Then in time I realised that if the glue spreads across the whole canvas, the entire surface is adhesive. So I prepare the canvas with a mixture of wood glue and paint, and in the making stage it’s a very lively adhesive surface that I can attach stuff to. Afterwards I polish it so that the surface can’t get easily affected by water or mist. I apply layer after layer, so it’s a slow process of applying, then sanding, applying, then sanding. And the blackness has that tar-like, bitumen quality, which makes me think of the bog bodies in Ireland – human bodies mummified in peat.

DODD: Yes, there’s that ancient peaty earth aspect – Seamus Heaney’s Tollund Man. But it’s also the sci-fi blackness of outer space that is conjured.

MARX: I’ve always thought that there are two neutralities or voids in making work. The white void is the gallery, which is the space in which there is nothing until there’s something. The black void is the void of theatre, in which I’ve worked extensively. And in the theatrical space, everything is there and gets revealed through light and narrative. So everything is already present and comes to light as it gains significance. It’s like history. What I love about these maps is that I’m speaking into this vast history where everything is already there, but I’m threading the fragments into a kind of a narrative. That’s how I think about the blackness.

DODD: And then there are the hovering shapes against the plain of blackness. They strike me as being very architectural structures – or exercises in a kind of impossible architecture. There’s that mise en abyme sense of infinite recursion – an interior within an interior within an interior…

MARX: In map convention the ‘interior within an interior’ logic speaks to the tradition of a ‘key’ – the smaller map informs the larger. In these works they inform, contradict, layer, even intersect each other. Most of my work stems from an interest in indexical objects – self effacing objects that point elsewhere. A map doesn’t point to itself; it is a guide to a broader landscape beyond itself, so in theory, changing the map changes the way we depict and know the world.

In making these maps, I’m asking myself: If maps aim to represent something complex through simplification, does it follow that complicating the map could complicate the terrain? If I can somehow complicate a map’s flatness, does it start to hint at a more complex dimensional world view? Does complicating the flat sheet – the Mappa Mundi – imply a re-wilding of sorts, returning ‘territory’ to wilderness?

4

–

IMAGES: